Keeping your shoulders safe can be more challenging than protecting your hips. The shoulder joint does for the arm what the hip joint does for the leg. It connects the limb to the trunk. Both are ball and socket joints, which allow for the greatest range of motion of any joints. However, there are two key differences that explain why your arms’ range of motion is even greater than your legs’. The same differences also explain why your shoulders can be trickier to keep safe than your hips. However, the “spreading your wings” movement we learned last week can help us move our shoulder blades in such a way as to keep the whole shoulder girdle safer.

The shoulders are less stable than the hips

The first difference significant is that the shoulder socket is much more shallow than the hip socket. This allows our arms to move farther without being limited by the arm bone touching the edge of the socket. The socket is so shallow that a special group of muscles need to stabilize the head of the arm bone. These muscles are collectively called the rotator cuff. The second significant difference is that the shoulder blade, which contains the shoulder socket, is not directly connected to the spine. The hip socket is located in the hip bone, which is firmly attached to the sacrum, which is a part of the spine. In contrast, the shoulder blade connects to the collar bone, which connects to the breast bone, which connects to the ribs, which in turn connect to the spine. Got all that?

As a result of the second difference, we can locate our arm in space not only by rotating the upper arm bone (the humerus) in the shoulder socket, but by moving the shoulder blade relative to the trunk. This is part of the reason for the greater range of motion of the arm versus the leg. However, when the movement of the arm bone in the shoulder socket and the movement of the shoulder blade relative to the trunk are not properly coordinated, it is quite easy to injure the shoulder.

Shoulder injuries are not inevitable

Shoulder injuries are not inevitable, and understanding the anatomy of the shoulder girdle can help us understand how to avoid these injuries. The basic idea is that moving our shoulder blades too far out of neutral alignment (up, down, towards, or away from the spine) is problematic for two reasons.

- When we move the shoulder blades too far out of neutral we can injure the muscles that connect the shoulder blades to the ribcage and spine. Muscles get weaker the more they lengthen, making elongated muscles more prone to injury.

- When we move the shoulder blades too far, we can also seriously damage the tendon of the supraspinatus, one of the rotator cuff muscles. The reason for this is that extreme linear movement of the shoulder blade prevents the shoulder blade from rotating. Upward shoulder rotation, however, is the best way to protect the supraspinatus tendon from getting pinched when we lift our arms overhead.

Try it now: Movements of the shoulder blades

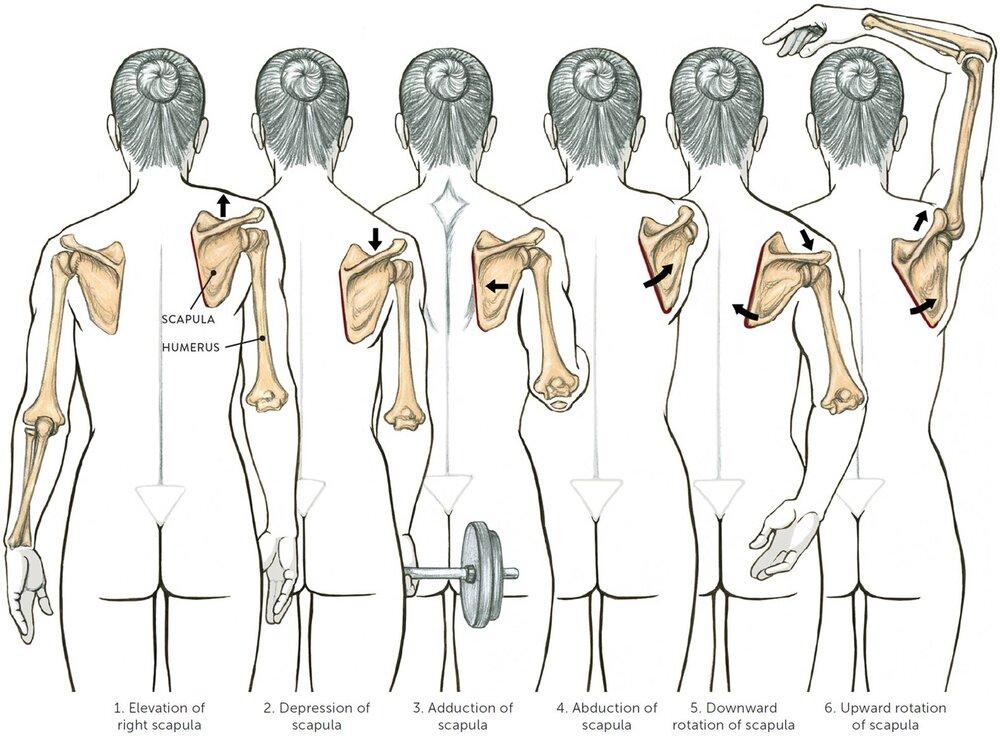

To feel how far your shoulder blades can move relative to your torso, hike your shoulder blades up towards your ears (called “elevation”). Then pull them straight down the back (“depression”). Hug them towards the spine (“adduction”), and then slide the shoulder blades away from your spine by rounding your back (“abduction”). Be very gentle with these movements as it is surprisingly easy to strain one of the opposing muscles if you move the shoulder blades too far. Though these movements are clearly possible, in general we are better off limiting them.

The 4 linear shoulder blade movements and 2 rotational movements; Image source: unknown

Keeping your shoulders safe: Rhomboids

Not letting the shoulder blades slide too far is important for the safety of the muscles that connect the shoulder blades to the ribcage. Of these, the muscles most easily damaged are probably the rhomboids, which connect your shoulder blades down and in towards the spine. If you have ever had an injury that felt like it was below the inner edge of your shoulder blade, that was probably a rhomboid injury.

There is no true joint between the shoulder blade and the rib cage. There is no strong connective tissue here like a ligament or a joint capsule. When the arms are weight-bearing, the transfer of the torso’s weight into the arms is borne almost entirely by the muscles that connect the shoulder blades to the ribcage and spine.

When you allow your shoulder blades to move from their neutral position while weight-bearing, the weight-bearing muscles elongate. The feeling of this can be described as hanging out in your joints. Elongated muscles are inherently weaker than muscles at resting length. Being weaker when elongated, these muscles are significantly more prone to injury.

One common problematic direction is the sliding of the shoulder blades up towards your ears. The other is allowing them to “wing” above your rib cage. If done with poor alignment, Downward Dog, Plank, Cobra, and especially Chaturanga Dandasana have significant potential to damage your shoulders. This is why doing a lot of Vinyasas can be problematic for your shoulders. Vinyasas require good shoulder blade alignment, but they are also quite exhausting. When you are tired, and doing your twentieth vinyasa in a class, you may be tempted to just hang our in your joints because it’s easier. It is, but it is also dangerous.

Keeping your shoulder blades neutral requires awareness

Keeping your shoulder blades in neutral is more difficult than it sounds. The most neutral position of the shoulder blade is in the middle of its range of motion. From here by definition it can most easily move in any direction. The upside is that maintaining the shoulder blades in their neutral position protects the muscles that connect the shoulder blade to the torso. It also distributes the work of holding up the body with your arms more evenly.

So how do you get your shoulder blades into a safer place in poses like Chaturanga? Forcefully moving them in the direction opposite from the direction in which they want to go is NOT the answer. The idea of finding the place in the middle is very important here, and then creating active but gentle muscle engagement. Imagining hugging your shoulder blades onto your rib cage is one good way to do just that.

So how do you maintain neutral shoulder blade alignment in Chaturanga? You need to learn to move your whole torso forward as you bend your elbows instead of lowering straight down. You can verify this easily. While standing, extend your arms out in front as if you were in Plank. Then draw your hands back to the shoulders. Notice that you have to pull the shoulder blades up to do that. Extend the arms again. This time pull your hands back and down towards your bottom ribs. Notice how your shoulder blades can now more easily stay in neutral. To get your hands near the bottom ribs in Chaturanga, you will have to move the rib cage forward because your hands are anchored to the floor. The best instruction I have found to initiate that movement is to float your breastbone forward to begin Chaturanga. Another good instruction is to extend forward through the crown of your head. A third on is to “land like an airplane, not like a helicopter”.

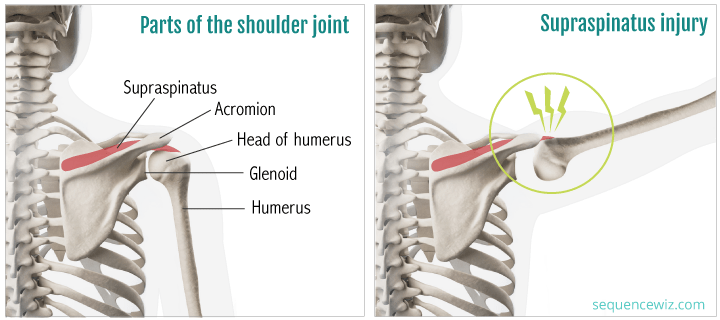

Lifting your arms without spreading your wings can pinch your supraspinatus tendon. (Source: sequencewiz.com)

Keeping your shoulders safe: Supraspinatus tendon

There is one more important movement of the shoulder blade, called upward rotation. This one we actually want to do intentionally, because it is crucial for protecting your supraspinatus tendon. This upward rotation requires freedom of movement of the shoulder blade relative to the ribcage. In turn, this necessary freedom of movement also allows for the other four, generally pointless and potentially dangerous, linear movements of the shoulder blade discussed above.

What is upward rotation and why is it important? In upward rotation the shoulder blades remain in place, but the bottom tips of the shoulder blades rotate outward and up. (At the same time, the inner top margins of the shoulder blades rotate down.) Lifting the arms overhead without allowing upward rotation of the shoulder blades can pinch the supraspinatus tendon. It gets pinched between the humerus and the acromion, a protrusion on the shoulder blade located above the shoulder socket.

Rotating the bottom tip of the shoulder blade out and up allows the acromion to rotate out of the way as well. So why don’t we let the shoulder blades rotate when we lift our arms? The answer lies in our desire to go farther and to feel more accomplished.

If we want to lift our arms as high as we can get them, elevating our shoulder blades is the solution. Unfortunately, elevating the shoulder blades prevents the upward shoulder blade rotation necessary to protect the supraspinatus tendon. The result is that the supraspinatus tendon gets pinched between two bones. Minor tendon injuries don’t usually cause immediate pain because tendons have few if any pain receptors. Thus we get no useful negative feedback to tell us to stop pinching. However, when you pinch your supraspinatus tendon every time you lift your arms, those cumulative small injuries can slowly turn into a serious one.

Preventing the pinch requires awareness

Hiking the shoulder blades up prevents the upward rotation of the shoulder blades. Thus some well-meaning yoga teachers instruct you to pull the shoulder blades down the back. This, however, is even more dangerous. We all tend to think that the opposite of something problematic must be its solution, but that is not generally true. Shoulder blade alignment is a really good example of the inaccuracy of this belief. Actively depressing the shoulder blades also prevents the upward rotation of the shoulder blades. What is worse, depressing the shoulder blades actively jams the acromion down onto the arm bone, now pinching the supraspinatus with even greater force.

You can verify this for yourself by lifting your arms overhead and experimenting with your shoulder blade placement. Facing a mirror, lift your arms alongside your ears (as in Hasta Tadasana). Notice the amount of space between your upper arms and your neck. If there isn’t much, your shoulder blades have slid up the back. This is less than ideal, and you may already feel a pinching sensation in the back of the shoulder joint.

If there is a fair amount of space, consciously and carefully draw your shoulder blades up towards the ears. Notice how the feeling of spaciousness in your neck and upper shoulders disappears. Also notice if you can feel a subtle pinch in the back of the shoulder joint. Depending on the shape of your acromion, this may or may not be a problem here. If you feel a strong pinch, back off immediately, but gently.

Now move your shoulder blades straight down the back, but proceed with even more caution! If you draw them down too far, you will probably notice a pinching sensation in the outer back of the shoulder joint, even if you didn’t before. As soon as you feel a pinch, back off. That pinch is potentially quite dangerous. It’s the supraspinatus tendon getting pinched between the acromion and the arm bone. Repeatedly jamming the shoulder blades down the back with the arms raised overhead can do serious damage to your rotator cuff.

Learn to rotate the shoulder blades up to keep the supraspinatus safe

In general it is best for the health of the shoulders to learn to stabilize the shoulder blades relative to the ribcage. That means neither allowing them to move too far up, down, in, or out along the ribcage. Preventing linear movement allows the rotational movement that protects your acromion.

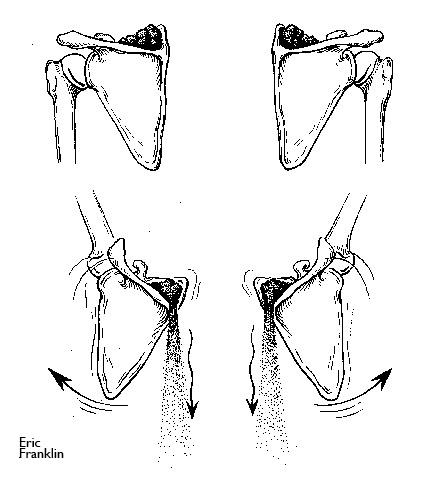

Now lift your shoulder blades back up towards your ears. The adjustment to make to avoid the tension in the neck and the pinching in your rotator cuff is to rotate the bottom tips of the shoulder blades out and up. When that happens, the top inner corners of the shoulder blades move down.

Here is one way to visualize the desired alignment in Hasta Tadasana. Imagine having piles of sand sitting on the top inner corners of your shoulder blades. Imagine pouring out the sand to allow the inner margins of your shoulder blades to slide down your back. This is how you can activate upward shoulder blade rotation after the fact if you have lifted your arms with too much neck tension.

“Dump the sand” to protect your supraspinatus tendon; Image source: Eric Franklin

Releasing the inner margins of your shoulder blades feels like they are sliding around the ribcage towards the front of the body. That is what we want here. Another popular instruction to undo the pinch is to create an outward rotation in the upper arms. (Outwardly rotating your upper arms means rotating the elbows towards each other. This causes the shoulder blades to rotate away from each other.)

However, it is also possible (and even better) to prevent the pinching in the first place, rather than to undo it after the fact. Spreading your wings (last week’s theme) is one excellent way of initiating the upward rotation of your shoulder blades. Spreading your wings also helps you lift your arms in a biomechanically more effective way that does not involve tensing the back of the neck.

Sometimes you need to back off to avoid the pinch

Learn to listen for the pinch in the back of the shoulder and find ways to make space there instead. Undoing the pinch is a great example of my favorite general alignment instruction to make space wherever there is a lack. Not allowing your shoulder blades to jam up towards your ears in Cobra is another great example of this principle. And not jamming your shoulder blades all the way down in Cobra instead is yet another one.

Learn to connect the shoulder blades onto the ribcage to keep them near the middle of their range of motion. This is where they feel most spacious. Learn also to allow the shoulder blades to rotate up to avoid the pinching in the back of the joint. If you can do both, your shoulders have a much better chance of staying healthy long-term.

Lastly, sometimes the only way to avoid the pinch is to push less far into a pose. This is particularly important in backbends where the arms rotate up and back past your ears. Think Bow Pose and King Pigeon Pose. But even here, dumping the sand out of the inner upper corners of your shoulder blades can keep you safe. Spreading your wings has the same effect, if you find that to be an easier cue to follow.

Thank you so much for this enlightening article.

I have three questions:

1. So the only thing can happen to shoulder blades when arms are overhead is outward rotation. Right?

2.Would the shoulder blades be rotating outward if didn’t try to do anything with them and just let them go where they did naturally when I took arms overhead?

3. As this is about outward rotation of scapula when arms are overhead, I assume this applies to every yog pose in which arms are overhead like down dog, upward bow. Right? But we often hear a cue in upward bow that is,”squeeze bottom tips of shoulder blades towards each other. So is that cue in upward bow wrong and potentially dangerous to the supraspinatus?

Hi there, thanks for your questions.

1. Not sure what you mean by ‘can’. There are other things that can happen with the shoulder blades when arms are overhead, but all the other options are potentially more problematic than outward rotation.

2. Technically yes. But most people lift their arms in such a way that they prevent the beneficial rotation of the shoulder blades. Just because you didn’t try to do anything with them doesn’t mean that you didn’t do anything.

3. Yes, it applies to every yoga pose and anything else you do in your life that requires arms overhead. I have not heard a “squeeze bottom tips of the shoulder blades towards each other” in upward bow pose (wheel pose), but that does seem like a potentially problematic instruction. I just tried it out, and when I squeeze my shoulder blades towards each other in wheel pose I can lift up higher, but I feel a pinch in the shoulder joint. Remember, yoga instructions are not necessarily designed to keep you safe. Instead, they may be designed to push you farther into the pose. An instruction to reach your fingertips to the ceiling in Hasta Tadasana is also not designed to keep your shoulder safe. It’s designed to get your hands higher.

So how do you know which instructions to follow and which to ignore? With some awareness training, it is quite easy to feel the pinching sensation near the outer top margin of the shoulder blade. That pinching sensation is in all likelihood a supraspinatus injury in the making. If you focus on maintaining space there, you should be fine. The feeling of space there is much easier to notice than whether your shoulder blades are rotating properly or not, so just create space in the back of the shoulders when there is a lack. And if following an instruction causes you to lose that space and feel a pinch, then ignore that instruction or at least back way off.

Thank you so much for the reply.

1. I meant “the only thing should happen”. Anyway you got it right I got my answer.

3. I have been doing this “squeezing the bottom tips of shoulder blades” thing but I did not feel pinching sensation. Maybe the inflammation or tension has yet not gone bad enough to make me feel it. But I am going to avoid that cue from now on.

Just to make sure, the cues which bend the thoracic spine like lifting the chest or firming the shoulder blades into the ribs, in poses like upwards bow don’t create any problem for supraspinatus, right?

And I should avoid engaging lower traps in poses requiring arms to be overhead because lower traps depress the scapulas. Right?

1. Ok! :)

3. The best overall advice I can give is to make space everywhere in your body where you feel a lack. Not pinching the supraspinatus is one specific example of that. I would think that an instruction to “firm the shoulder blades into the ribs” is relatively safe. I am not sure I would say “avoid engaging the lower traps”, but a strong engagement of the lower traps (“pulling the shoulder blades down the back”) has a good chance of pinching the supraspinatus. One last thing: The gap between the acromion and the head of the humerus varies dramatically from person to person. This means that some people’s supraspinatus is quite safe even with poor biomechanics. I have at least one student who has had her acromion shaved down surgically because even with good biomechanics she could not avoid damaging her supraspinatus. So again, learn to listen for a lack of space in the back of the shoulder joint, and when you feel it, make space there. Good luck!

Thank you sir.

One more cue for upward bow I came across was “broaden or widen the shoulder blades across the back”. This probably means broaden shoulder blades away from the spine i.e. the abduction of shoulder blades. Right? If so, this cue could be problematic too bc what we want here is outward rotation not abduction. Right?

P.S.: In above article whilst explaining the movements of scapula you have mentioned ‘aDduction’ in place of ‘aBduction’ by mistake.

Hi Abhishek,

yes, broadening the shoulder blades sounds like an instruction to abduct. In my experience, trying to move the shoulder blades linearly in any direction tends to make it more difficult to rotate them, and upward rotation of the shoulder blades is what most of us need to keep the shoulders safe when the arms are overhead. Thus I avoid giving directional cues for the shoulder blades in general. However, a cue of broadening the bottom tips of the shoulder blades could be quite useful, as that encourages upward rotation. Perhaps that is what the teacher giving the cue meant, and perhaps also what they do. However, I would suggest that “broaden the bottom tips of the shoulder blades” is a better clue. Even better might be to say “rotate the bottom tips of the shoulder blades away from each other, because that doesn’t imply a linear motion. All the best!

Thank you sir.

I would just like to let them rotate upward on their own as they automatically and naturally rotate upward when arms are overhead. I would not want to try to rotate them manually and would rather just let them rotate on their own. This is bc I think manually rotating them upward or broadening bottom tips would tighten or stiffen the serratus anterior which might be wrong for a person with hunched back as it would add to the existing forward head posture of that person. Am I correct to think so?

Hi Abishek, yes, if indeed your shoulder blades rotate upward naturally when you lift your arms overhead, that’s great. Unfortunately that’s not the case in many people. Also, obviously some muscles need to contract concentrically for the arms to lift overhead. I would argue that the serratus anterior is actually a good muscle to add to the lifting of the arms through the outward rotation of the shoulder blades.

Your thinking that the engagement of the serratus anterior contributes to hyperkyphosis (the hunchback) and head forward position is in my experience incorrect. The serratus anterior is actually a great muscles to engage to REDUCE hyperkyphosis and head forward position. Because it is a generally underutilized muscle that counteracts the most common postural misalignment I think it’s worth while learning how to engage it.

Thank you very much indeed for your validation sir.

Could you please name some poses(other than those with arms overhead) in which we should engage serratus anterior?