Forward bends can be quite problematic for the lower back. When we bend forward, we tend to do too much of the movement in the lower back. The lumbar spine is quite mobile in this direction, but excessive movement here is a frequent cause of back pain. Lower back pain in turn is the most common health complaint in the US. Last week we focused on alignment in the upper back and neck in forward bends. This week we will focus on lower back and hip alignment.

Understanding herniated discs

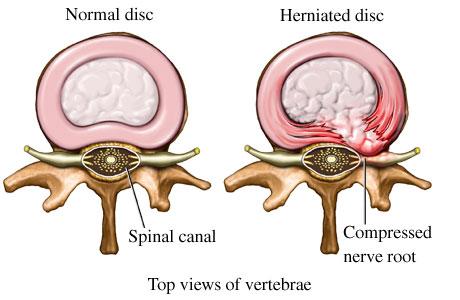

We often don’t know what actually gets injured when we hurt our lower backs. However, one common injury from excessive forward bending is a herniated intervertebral disc. Why are herniated discs an issue? When a disc bulges or ruptures, it can compress a nerve root exiting the spinal cord, triggering significant and sometimes even debilitating pain.

Unlike the nerve roots, the spinal cord itself is relatively well protected from disc herniation. While the spinal cord lies directly behind the discs, a long tough ligament called the posterior longitudinal ligament protects it from bulging discs. Because this ligament lies within the spinal canal, it is by necessity narrow, which means that it cannot protect the nerves exiting sideways from the spinal cord. A herniated disc typically bulges to the rear and to one side because the longitudinal ligament generally prevents it from bulging straight back. So while the spinal cord is protected, the nerve roots are not, and their compression can trigger severe pain.

The majority of disc herniations occurs between the two lowest lumbar vertebrae (L4-L5) or between the lowest lumbar vertebra and the sacrum (L5-S1). A herniated disc is also commonly referred to as a slipped disc, but this is a misnomer as the discs cannot slip. Each disc is fused to the vertebral bodies above and below.

A ruptured or herniated disc is a more severe injury than a bulging disc. In a bulging disc the tough outer layer of the disc (the annulus fibrosus) remains partially intact. But even the majority of disc herniations heal within weeks or months, and very few require surgery. Nonetheless we are better off not injuring them in the first place. In addition, sometimes the pain can become chronic because we keep re-injuring a disc through continued poor biomechanics.

A healthy and a herniated disc, showing a typical pattern of damage.

Keeping your back safe

So what can you do to keep your lower back safe in forward bends?

1. Stop following the path of least resistance

When we move unconsciously, we use strong muscles to move flexible joints, and we avoid using weak muscles to move tight joints. Repeating the same movement patterns rather than creating new ones requires less mental effort. Using strong muscles to move flexible joints also requires less physical energy than using weak muscles to move stiff joints. Both reasons relate to the fact that evolutionarily speaking, we are built for efficiency. But efficiency, while it helps prevent starvation, does not increase well-being and does not prevent injuries.

Forward bends intend to flex your hips and your entire spine. But because of tight hips, most of us do too much of the forward bending in the lower back, and not enough in the hip joints. The longer we favor flexing the spine instead of the hips, the tighter our hip joints get. And the tighter the hips, the more common and severe lower back pain becomes.

Don’t believe me that you underuse your hip joints? Try this simple exercise: Lie on the floor and notice that your lower back is off the floor. Inhale one knee towards your chest and hold your shin with your hands. Notice that your lower back is now in contact with the floor. This movement is a very gentle hip flexion that doesn’t even stretch the hamstrings because of the bent knee. Yet even here we do as much of the work as we can in the lumbar spine instead of the hip joints.

To stop following the path of least resistance in forward bends means learning how to do an anterior hip tilt. Anterior hip tilt means moving the tops of the hips forward towards the knees. This movement increases flexion in the hips, while decreasing it in the lower back.

2. Avoid bending forward and twisting your spine simultaneously

In a simple forward bend, the discs bulge straight back into the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. This usually prevents disc damage in this direction. If you combine a forward bend with a spinal twist, the direction of the force is to the back and one side, where there is no ligament to protect the disc. Thus bending forward while twisting with too much force is particularly likely to injure a disc.

The solution, part 1: Avoid poses that are designed to bend and twist your spine at the same time, or modify them to reduce the twisting motion. For example, in Janu Sirsasana, don’t bend forward directly over the straight leg because that requires a twist to that side. Instead, bend forward inside the straight let, keeping your breast bone pointing in the same direction as your pubic bone, centered between your hip crests.

The solution, part 2: Avoid bending forward in spinal twists, which is unfortunately often the path of least resistance. In poses such as Marichyasana III, notice the tendency to collapse the front of your chest as you twist in order to get your arm more fully around your bent leg. When your chest collapses, your back is bending forward. To reduce the forward bend which makes the spinal twist more dangerous, inhale your breastbone away from your bellybutton and send energy down into your sit bones and up and out through the crown of your head. When you do this, notice the increased feeling of space along the spine and the reduction of pressure in your lumbar discs. Also note that you can actually twist a little farther when you don’t forward bend at the same time, though that is not the main point! The health of your spine is.

3. Work on lengthening your hamstrings in poses that make it impossible to cheat

If your hamstrings are particularly tight, just building awareness may not be enough. Neutral hip alignment in many poses is simply impossible if your hamstrings are tight. If you use standing or seated forward bends to try to lengthen your hamstrings in order to reduce the workload on your lower back, you may actually injure your lower back instead! Not so useful.

The solution is to lengthen your hamstrings in poses that don’t allow you to stretch the lower back instead. Simply put, this means reclining hip stretches, because when you lie on your back and flex your hips, you can’t really cheat by rounding your lower back. Lying on the floor, you can flex your lower back only a few degrees before it flattens against the floor and can go no farther. Resting against the floor also means that your lower back is perfectly safe here. In seated or standing forward bends, by comparison, it tends to receive most of the strain.

Do your hips flex less than 90 degrees in Supta Padangusthasana (reclining straight-legged hamstring stretch)? Then I would suggest avoiding standing and seated forward bends entirely for the time being. Instead, when your teacher instructs any seated forward bend, lie down on your back facing a wall. Then bring your legs up a wall in the same shape as what your teacher is instructing for the seated variation. Dial in the stretch intensity by how close you place your sit bones to the wall.

Most of us do suffer from tight hamstrings, but fortunately lengthening muscles is relatively straightforward. Noticeable changes happen within a matter of weeks if you are consistent in your exercises, emphasize surrender in your stretches, and practice with reasonable intensity.

4. Strengthen postural muscles that protect your spine

Recent research points to a correlation between persistent back pain and poorly functioning multifidus muscles. Never heard of them? Don’t worry, most people haven’t. Each multifidus muscle connects the transverse process of one vertebra to the spinous process of the next higher vertebra, or the one above that. These muscles, when they function well, can keep the vertebrae in more neutral alignment, and in particular, can prevent excessive spinal flexion and thus can reduce the internal disc pressure that can lead to herniations.

So, how can you learn to strengthen your multifidi if they aren’t already doing their job? One way is to keep your hips level in poses in which you are tempted to lift one up behind you. These poses are 3-legged Table, 3-legged Down Dog, and Warrior 3.

5. Tune up your multifidi

Come into table, and inhale one leg up. Notice whether you lifted your hip when you lifted the leg. Most of us do, because it allows us to lift the leg higher with objectively less effort. It also creates a subjective reduction in effort. It allows us to use strong muscles we are good at engaging, while avoiding engaging muscles we are not good at engaging. In other words, moving this way makes us feel efficient and accomplished, as it feels like we are going farther with less effort. But guess what: Those muscles you are avoiding engaging by lifting your hip when lifting your leg? Those are your multifidi.

Observe what happens when you slowly lower the hip of the lifted leg towards neutral. To make this happen, you can focus on lifting more through the inner thigh while letting the outer hip descend. As the hip lowers, can you feel a “cinching down” sensation ripple along your spine? It’s quite a deep sensation, below the big superficial spinal muscles. If so, those are your multifidi engaging. Simply add these 3 poses to your practice and focus on keeping your hips more neutral in them. If you do, you can have a significant impact on your spinal health and your overall wellbeing. I always inhale one leg up behind me before stepping forward from Down Dog, and I always emphasize relatively neutral hips in this movement. This way I build multifidi exercises into each yoga practice.

6. Lengthen your spine when you bend forward

Keeping your spine long helps protect your spine in forward bends as well as in backbends. The more the front edge of the disc compresses, the greater the internal disc pressure, which is the direct cause of herniated discs. (The pressure can rise from 17psi in a lumbar disc in a reclining person to over 300psi when lifting a heavy object with a rounded lumbar spine.) Keeping your spine long maintains more space between the vertebrae, thus reducing pressure inside the discs. How do you keep the spine long in forward bends? Engage your multifidi.

However, just telling people to engage their multifidi doesn’t work, because these deep postural muscles are challenging to engage consciously, even for people who actually know that they exist. Instead I use a more experiential instruction to create the necessary contraction.

One instruction for seated forward bends I give is to think of the movement as a lifting up and over, rather than a bending down. To make this concept more intuitive I use the image of a cresting and crashing wave. Have you have ever watched a crashing wave closely? Have you noticed how the water actually runs back and UP the front surface of the wave before moving forward and finally crashing down? Turning a forward bend into an act of “lifting up, over, and forward”, instead of collapsing down, quite naturally lengthens the spine and helps protect it. If you feel energy moving up along the spine, if you feel a “cinching down” rippling up the spine, you have figured out how to use your multifidi.

7. Practice with appropriate intensity to keep your back safe

The final point I want to emphasize for safe forward bends here is that forward bends have a cooling, down-regulating effect. They increase your capacity to relax and surrender. While seated forward bends appear in most beginner’s syllabi, they have great potential for causing injury when done with poor alignment and with too much effort.

Straight legged seated forward bends are particularly problematic. The extended knees tighten the hamstrings, causing the hips to rotate back even more than bent-knee seated poses. The other reason why straight-legged seated forward bends are particularly dangerous is that many people get preoccupied with wanting to touch their toes. This ego-gratifying but essentially meaningless detail tempts many people into stretching with too much force in poses like Paschimottanasana. And all that force goes into overstretching the lower and middle back, NOT into increasing hip and hamstring stretches. If you approach forward bends the way you do a Warrior I, for example, you are much more likely to injure yourself. But you completely miss the point of forward bends, to boot.

Great info thanks

You are welcome! :)

Wow, thank you, I’m about to sing up to your weekly, your knowledge and the clarity you have on sharing it is amazing. This was so very helpful in understanding where my current hip/ lower back pain may have been triggered

I am so glad you found the post useful. Let me know if you have any other questions. I also teach online private classes, if you want me to give you more personalized feedback on your back issues.

Thank you so much! Your ability to create a picture enabled me to really “see” what’s going on! May I ask what you mean in the next to the last sentence? “If you approach forward bends the way you do a Warrior I, for example, you are much more likely to injure yourself.” Thanks!

Hi Rebecca, thank you for your comment. What I mean by that is that seated forward bends are at least in part designed to down-regulate the autonomic nervous system, which is why they are commonly done right before Savasana. Warrior 1 is a much more active pose, designed to up-regulate rather than down-regulate. Warrior 1 is more about actively creating a shape, rather than surrendering into one, as is the case with seated forward bends. Though these days I do believe that every pose (except perhaps Savasana) benefits from some combination of surrender and engagement. However, in Warrior 1 an effective balance between surrender and engagement is skewed towards engagement, while in seated forward bends an effective balance is skewed towards surrender. I hope that helps. :)

Ugh this probably explains why I have crazy lower back pain since trying to do yoga several days a week :( Thank you! I will be avoiding forward folds for a long while. Are there any other exercises to lengthen the hamstrings? It’s not always easy to get to a wall to put my legs up, when others in class are doing forward folds.

When you can’t get to a wall, just do Supta Padangusthasana in the middle of the room, either with a strap around the foot, or with one or two hands behind the knee of the lifted leg, straightening the leg enough to get a juicy hamstring stretch. Here is a good illustration of the no-strap variation: https://www.yogajournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/hamstring_stretch_pillow_head_support.jpg?width=730

I have had lumbar spinal fusion and do gentle yoga 3 days a week. I try to take it easy on side bends and twists and have found it impossible to do Superman or just lifting either my head and torso or my legs an inch or two. It is extremely painful so what can I do instead? I will adjust to your advice on forward and seated folds and use a strap or the wall.

Hi Deidre, don’t do it if it’s painful. What happens if you just lift the head and upper torso and do the work with the middle-upper back, consciously NOT contracting the lower back, and leaving the legs on the floor? Also, how does Bridge work for you? If Bridge is pain free, just do that instead of Superman. Btw, I haven’t done Superman in over a decade, and actually had to look up what it is. I know it as Locust. When I do Locust, I always keep my legs on the floor and only engage the middle back, not the lower. Lastly, to strengthen the lower back stabilizers (which has been shown to reduce lower back pain) practice Pointer Dog with level hips. You will be tempted to lift the hip on the lifted leg side (because it’s easier AND you can lift the leg higher), but disrupt that pattern as it won’t strengthen your lower back.

Ohhhh! Now I know why I keep injuring my back and getting hip pain. This is exactly me. Thank you very much for writing this article.

You are welcome. Let me know if you have any questions or run into any difficulties.

I’m so glad to find this post I think after 3 years of mysterious re-injuries and constant pain that I’ve solved the riddle of why my hot yoga practice isn’t helping. My instructors have cued many of these points but I think I’m engaging too much when I forward fold. I do have a “L6” that’s fused so it probably doesn’t help the situation. It feels like my hamstrings can never stretch & hips are always tight/ feel good to pop often. I have been in physical therapy & chiropractic care and the chiro was wondering how I kept needing to come back. He told me to avoid twists but this makes more sense & correlate with the pain I’ve experienced. I do try to keep my hips level in warrior 3 and when doing bird dogs for PT (I think perhaps the same as pointer dog?) but I never considered during 3 legged dog I could be over extending the lifted leg. I am mindful to lengthen before janu but the collapsing and twisting makes perfect sense. I wish I found this sooner.

Hello – thank you for this article. For the images at the top, is one more advanced than the other? Or one demonstrates correct form (right?) vs. Incorrect (left?) Thank you.

Well, I guess one more thing.. if there was any way you could make video to accompany this article I’d be thrilled to watch it.

Thank you very much.

Hi Jay, good question. What do you think? I hope the answer is clear after reading the entire post. Many people would consider the left photo more “advanced”. I consider it misguided. It’s simply what happens when you try to go farther with less effort. You accomplish less of what really matters, you feel worse, and you risk injury. :)